1872年東京 日本橋

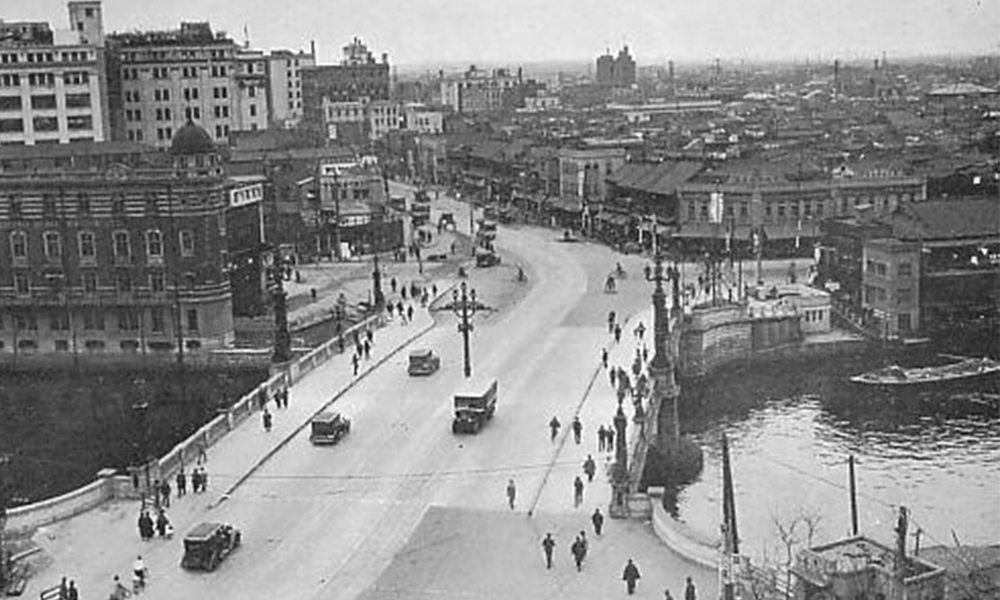

1933年東京 日本橋

1946年東京 日本橋

2017年東京 日本橋

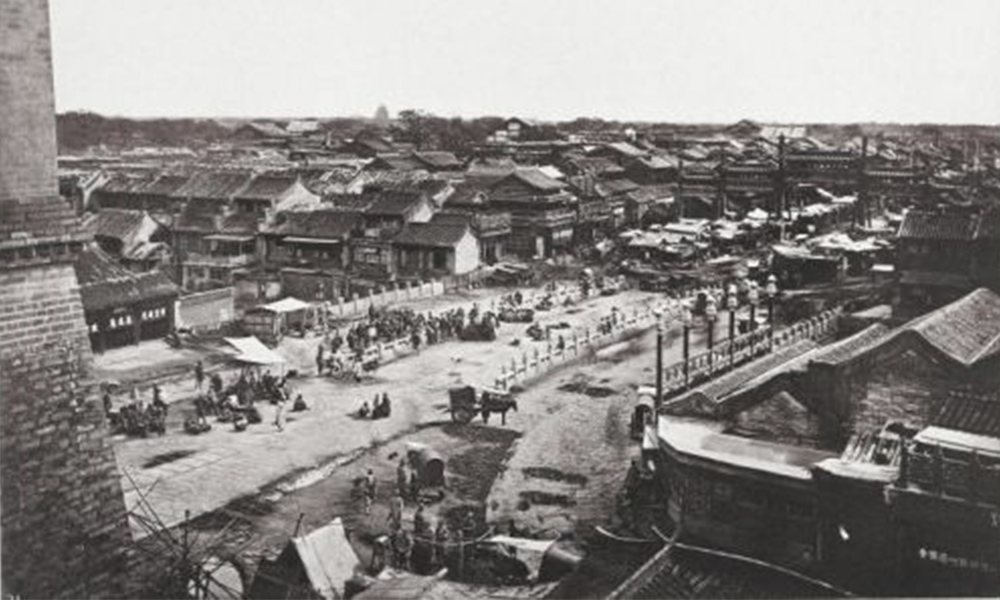

1872年8月〜10月北京 前門

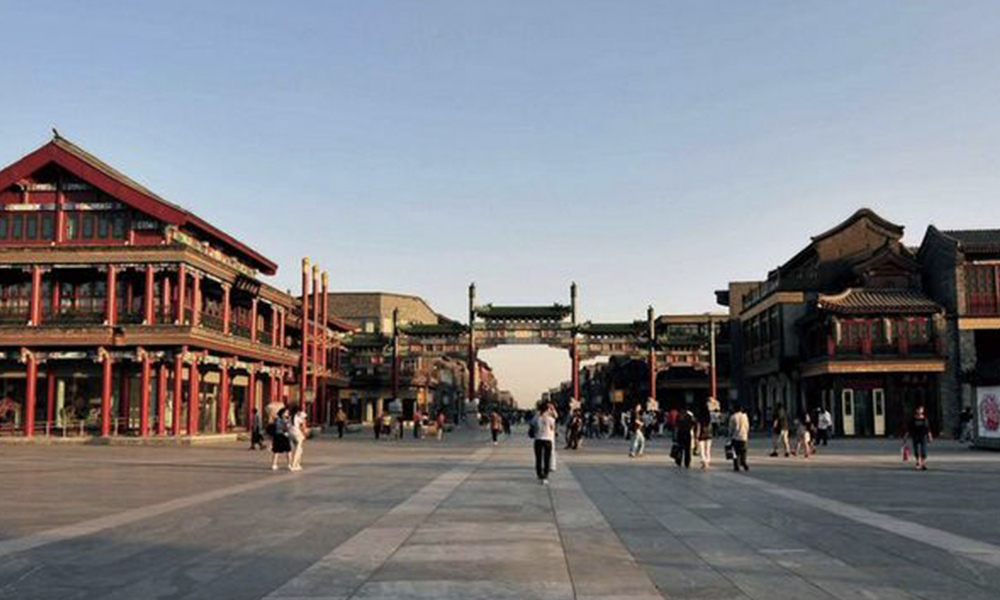

現在北京 前門

1949年前後北京 前門

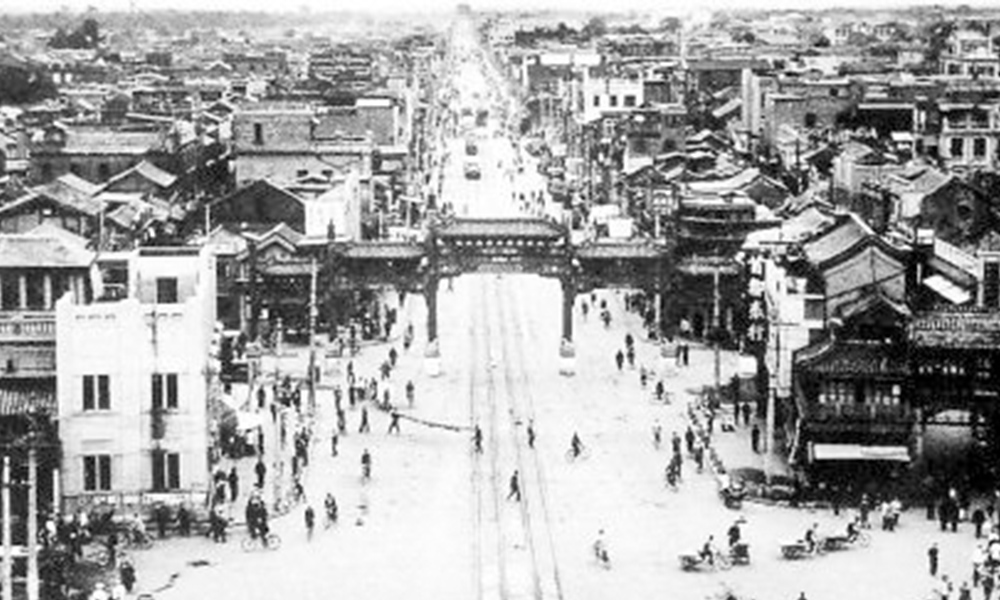

1930年代北京 前門

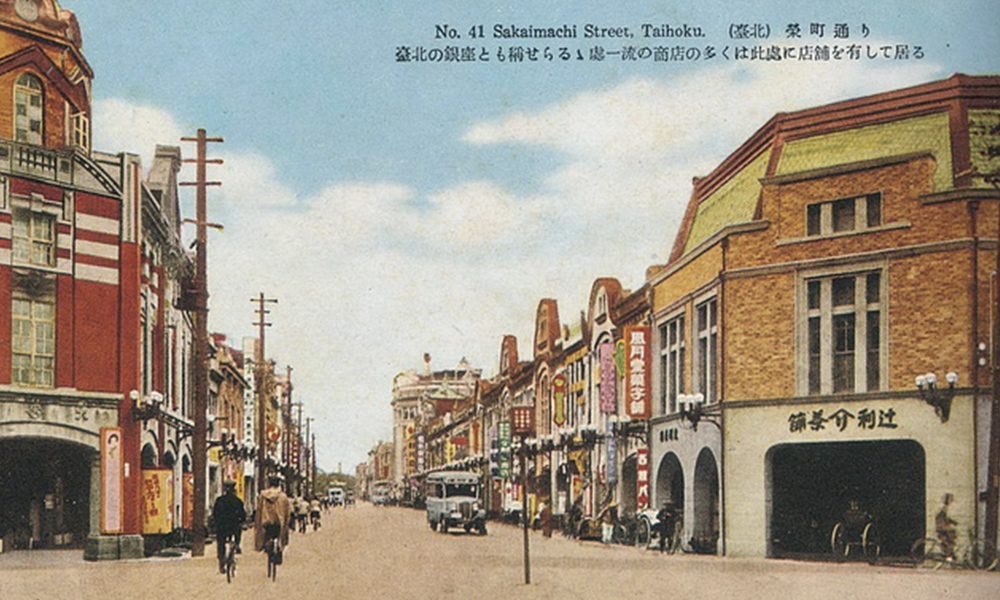

1895年台北 衡陽路

1930年代台北 衡陽路

1960年代台北 衡陽路

現在台北 衡陽路

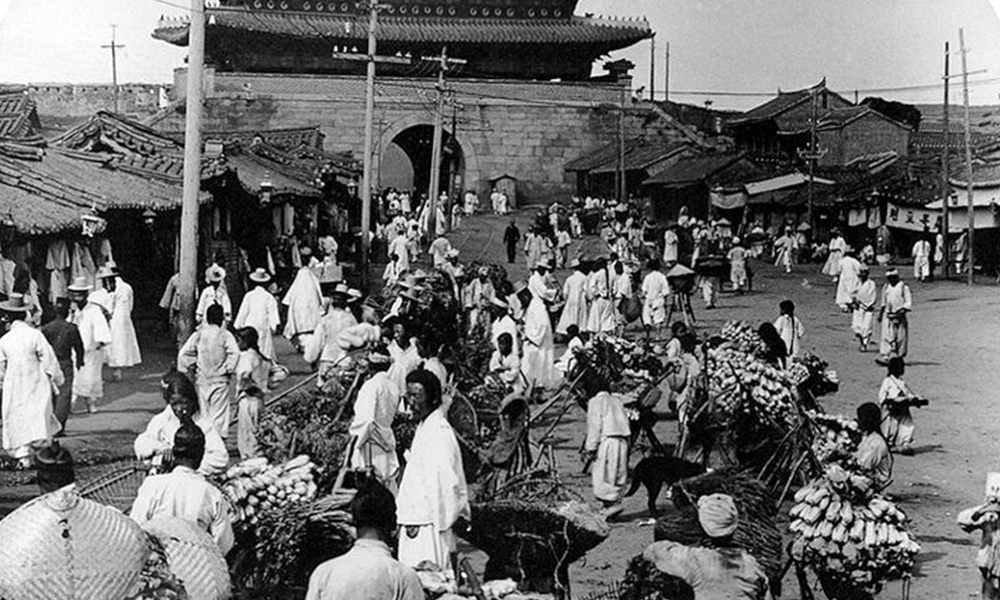

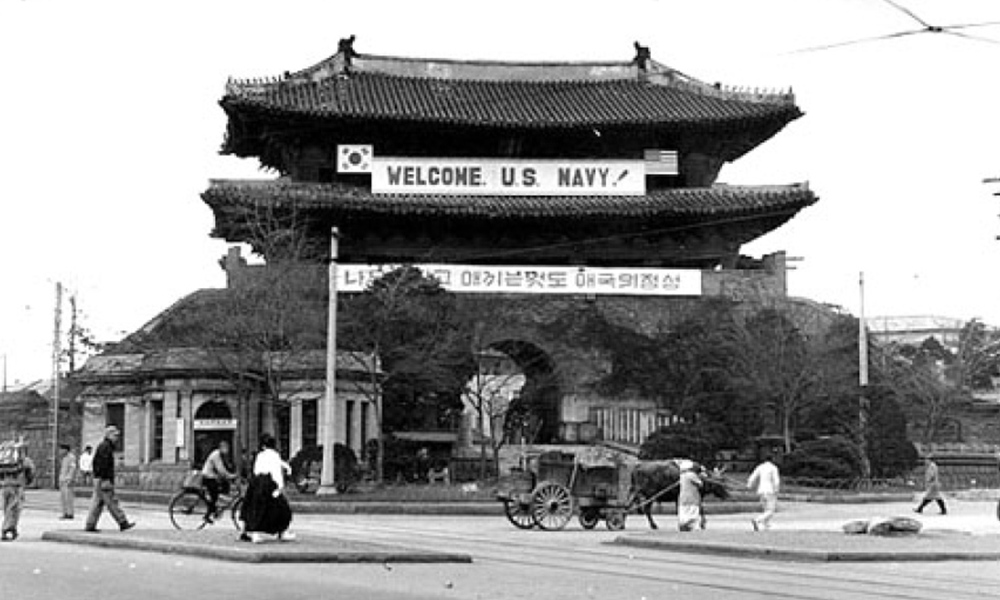

1904年ソウル 南大門

2006年ソウル 南大門

1950年ソウル 南大門

1940年代初ソウル 南大門

SungYong Lee

University of Otago, New Zealand

Of the various aspects that the new academic discipline of Reconciliation Studies examines, this essay pays attention to reconciliation at intra-state level and proposes agonistic pluralism as a framework for acknowledging and addressing some limitations of many intra-state reconciliation processes in Asia. Most countries in Asia have suffered from a variety of social tensions, ranging from military conflicts based on religious/cultural conflicts in Mindanao (Philippines) and Southern Thailand to ethnic minorities’ cultural under-representation in Taiwan and Japan. Despite various efforts to improve the tensions between different social groups, such efforts have faced many obstacles, including a high level of insecurity, social minority groups’ lack of political representation, the ruling groups’ authoritarian governance, and limited foci of the reconciliation process.

One of the prevalent issues is ‘the domination of narratives’ in the process of social reconciliation. It is an axiom that people’s perception and interpretation of things is influenced and restricted by the various social, cultural and practical situations in which people are located. Hence, while experiencing the same social conflict, people may develop their own way of understanding the conflict which is distinct from other groups’ understanding. Hence, there could be multiple narratives of the ‘truths’ in one conflict event. For instance, in 1989 when the civil war in Cambodia was coming to an end, Vietnam declared that it had withdrawn all its military forces from Cambodian territory. Nevertheless, many Khmer Rouge cadres believed that most Vietnamese soldiers still remained, but had simply taken off their uniforms. Hence, when many civilians were killed by the Khmer Rouge soldiers, the community residents thought it a massacre of innocents while the former Khmer Rouge commanders believe that it was an execution of hidden Vietnamese soldiers. Another relevant example can be found from Jeju, South Korea. A communist group’s uprising and the suppressive reaction of the government ended up with at least 14,000 casualties between 1948 and 1949. In interpreting the uprising, many identified it as the government’s brutal killing of and anti-humanitarian action against civilians whereas right-wing groups claimed it was the communists’ failed attempt at subversion.

The problem is that, in the discourse of reconciliation at domestic level in many Asian countries, a certain body (usually the state) utilises its power to discourage the expression and claims of different views on the controversy. One typical form of suppression of speech occurs when the ruling groups select one version of the narrative and set it as the standard history. In post-war Cambodia, the Hun Sen government’s anti-Khmer Rouge narratives have dominated all public discourse and the propaganda has played an important role in strengthening the government’s narratives. Another frequently applied type of suppression is to leave the nature of events unidentified or vague, in order to avoid further social tensions. In Jeju, South Korea, the official title of this chain of killings between 1948 and 1949 is ‘4.3 (or April 3rd) Incident’ with no descriptive definitions. Through such strategies, the promoters of social reconciliation aim to settle social disputes and, frequently, let people ‘forget’ the past and move on to future.

However, to what extent can reconciliation be promoted by imposing one version of the story or putting controversies under the table? Studies of Jeju, South Korea, as well as Cambodia confirm that decades after the conflicts, people still maintain their own narratives, feeling anxious that their ‘truths’ have not had the chance to get public acknowledgment. Rather than having one version of the historical narrative to define the meaning of a past issue, we may need to facilitate a safe and ambient space where people can develop their visions for reconciliation so that they can be expressed and exchanged.

The academic discourse of agonistic pluralism offers an insight to acknowledge and address the problems of such narrative domination. Agonistic pluralism has been primarily proposed and developed as an alternative to the concept of deliberative democracy. Deliberative democracy assumes that citizens’ preferences or opinions can be, or should be, formed and transformed through public deliberation and, through the process, a society can eventually reach a consensus on the issue at stake. Agonistic democracy or agonistic pluralism, in contrast, acknowledges and appreciates the centrality of conflict to human social actions. According to the proponents of agonistic pluralism, consensus or commonality is a difficult, fragile and contingent achievement of political action and should not be considered a normative or ethical precondition for good relations. A democratic society should allow citizens to freely contest the terms of public life.[1]

Then, how may the application of agonistic pluralism open an opportunity to develop a slightly different direction for facilitating reconciliation? I want to make three points, which are in line with the key note speech delivered by Barak Kushner in this symposium.

First, an agonistic perspective suggests that we need to redirect the state-centric process of mobilising social reconciliation into forms which allow for the coexistence of pluralistic narratives. The state-centric approaches frequently under-represent social minorities’ views and needs in pursuit of ‘settling accounts’, ‘healing nations,’ ‘restoring community,’ and ‘social unity.’[2] Multiple social actors should be encouraged to develop dissimilar actions and programmes for reconciliation, based on their own notions or versions of justice and reconciliation. Mutual understanding between divided groups can be promoted by exchanging different versions of narratives, without any intention to judge which one is absolutely right. In this regard, multiple methods for facilitating the exchanges of such diverse views should be promoted, reflecting local mechanisms. Many social reconciliation processes have failed to accommodate move diverse mechanisms for hearing and reflecting diverse views while primarily focusing on building formal and centralised forms and procedures, as can be seen in the sidelining of local processes in the post-war Timor Leste.

Second, the adoption of agonistic pluralism enables people to be more reflective of their own approaches to their counterparts in the reconciliation process. Agonistic pluralism acknowledges that a society is meant to be conflictual. In deliberate democracy, a high level of reconciliation frequently requires consensus on how to interpret the past. Nevertheless, too much expectation of consensus is likely to generate more conflict than reconciliation since a high level of reconciliation usually requires ‘their’ acceptance of ‘our’ narrative. Moreover, attempts to disregard the conflictual nature of social life is frequently associated with ignorance of the internal plurality of their counterparts. Under such circumstances, people are likely to perceive that one radical right-wing figure’s provocative statement represents the views of the whole social group, and this may undo all progress towards social reconciliation that has been made. In this regard, the application of agonistic pluralism questions if our own expectations of and attitude to social reconciliation are realistic and useful in achieving the goal.

Finally and related to the previous points, agonistic pluralism emphasises reconciliation as a process rather than outcome. To acknowledge and respect multiple-versions of the truth on a major social conflict or historical controversy requires careful arrangement, which reflects the social, structural and cultural contexts in each society/community. Hasty and politicised proclamations of vehement propagandas of different social groups are likely to generate further social tensions since people feel uncomfortable hearing something contradictory to their own beliefs. Many post-war peace processes confirm that the exchange of diverse views can be particularly risky in the aftermath of intense violence. However, studies also confirm that social prejudice and hatred are intensified where there is a lack of communication and interaction. Hence, the ambition to make a breakthrough in social reconciliation with an one-off event should be discouraged. Instead, agonistic pluralism encourages people to make a constant effort to create space where they can learn and acknowledge different views even though they don’t necessarily agree. Such a gradual process for nurturing mutual understanding itself is a step toward peaceful coexistence of different social groups and intra-state reconciliation.

Although my discussion has primarily focused on social reconciliation at intra-state level, the limitations of the centralised reconciliation process (ideologically based on the ideas of deliberate democracy) discussed above are also visible in many attempts for inter-state reconciliation. For instance, the public discourse in China, South Korea and Japan on the reconciliation between them and on the development of East Asia regional organisation presents issues like the domination of one narrative, (unrealistically) high expectations of reconciliation, a lack of acknowledgement of the other side’s perspectives, and ignorance of the plurality of the other side’s society. I believe that these issues are some of the reasons why the previous efforts for reconciliation in East Asia remain in rhetoric rather than in reality. In this regard, the implications of agonistic pluralism are not limited to intra-state issues.

Hence, further empirical studies need to be conducted to find out whether the ideas of agonistic pluralism can be materialised into the forms and procedures of social reconciliation that reflect various social contexts in Asia. Nevertheless, as a framework for visioning reconciliation, agonistic pluralism highlights that we need to let various social groups express their views and learn how to coexist with the people who have strikingly different views and narratives. Moreover, it warns that too much demand for ‘one nation’ or ‘social unity’ without such peaceful coexistence and mutual respect can be another form of social violence.

[1] See for example, Chantal Mouffe (1999) Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism?, Social Research 66 (3): 745-758; Rosemary Shinko (2008) Agonistic Peace: A Postmodern

Reading, Millennium – Journal of International Studies 36 (3): 473-491; Andrew Schaap (2006) Agonism in divided societies, Philosophy & Social Criticism 32 (2): 255-277.

[2] Andrew Schaap (2006) Agonism in divided societies, Philosophy & Social Criticism 32 (2): 258.